Back of the Napkin #2: Selection and Treatment Effects

This is part of an ongoing series by Brian Shih and Sebastian Park where we are exhaustively going through this interview with Jeremy Giffon on the Invest Like The Best podcast piece by piece and writing our thoughts along the way.

Fair warning: This piece includes a bit of inside baseball about, well, baseball. See the footnotes for all the gory details.

As a reminder, we’re planning to write one of these a week, and you can follow along here on Substack, or Seb’s LinkedIn. If you have any suggestions, comments, or want to join in as a collaborator on a particular topic, please reach out! You can reach Brian on Twitter and Sebastian on Twitter and TikTok.

Back of the Napkin #2: Selection and Treatment Effects

Last time we talked about The Perfect Business and the concept of leverage, and left off here:

And for the best ones [the best businesses], there's also this idea where the organizations are either selection effects or treatment effects. And so a selection effect would be Harvard or a modeling agency, where most of the prestige comes from picking the people. Whereas the seals [The Navy SEALs] or something like that, to some extent, will have a treatment effect, you become a different person by going through this program

And I think the best organizations do both. By virtue of being selected by the company, it really helps you for your entire career, and it gives you something. Like I really admire certain organizations where you can just tell someone's been at a consulting shop or something or been at a really good bank in just the way they write emails or the way they think or whatever.

And that's obviously a double-edged sword, but I really like this idea of you can just tell the polish and obviously, same with military people. Maybe there's a path to becoming a principal. I don't actually think you need that necessarily, but you should be certainly clear about it.

There's nothing worse than all these VCs that have never promoted from within to a partner, but then you ask associates and analysts there, and they're like, "Oh, I'm going to be a partner one day," and it's like, "No, you're just totally wasting your time."[1]

Continuing his commentary on the perfect business, Giffon dives into a tangent on selection and treatment effects. If you’re building a theoretical perfect business, should you focus on picking the best people, or training them?

Why not both? If we’re running this imaginary perfect business, unmoored from any constraints, hiring the best and extensively training them might indeed be the optimal thing to do. But for mere mortals operating in the real world without infinite time and budget, we must choose – it is almost certainly too massive an undertaking for companies to set out to do both.[2]

So which will it be? Selection or treatment?

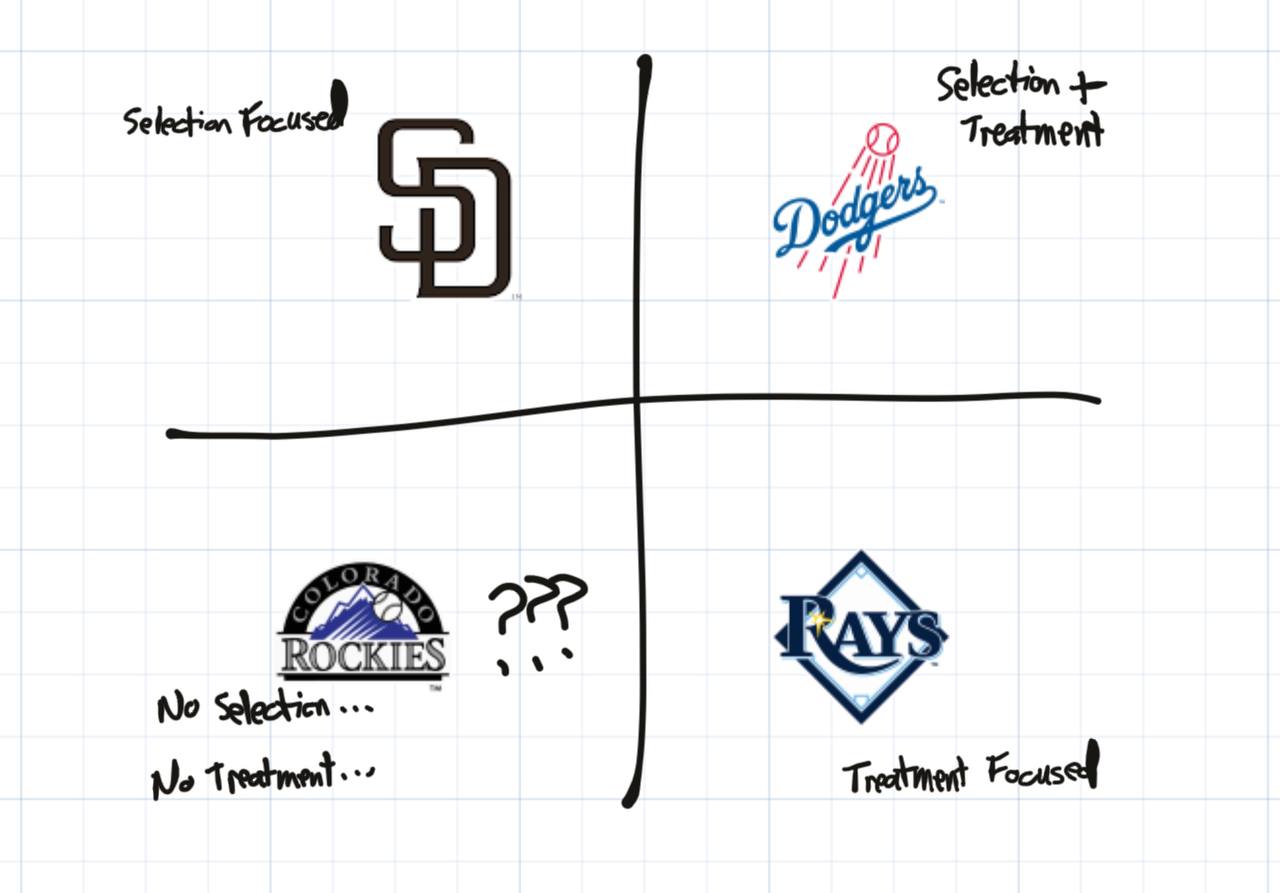

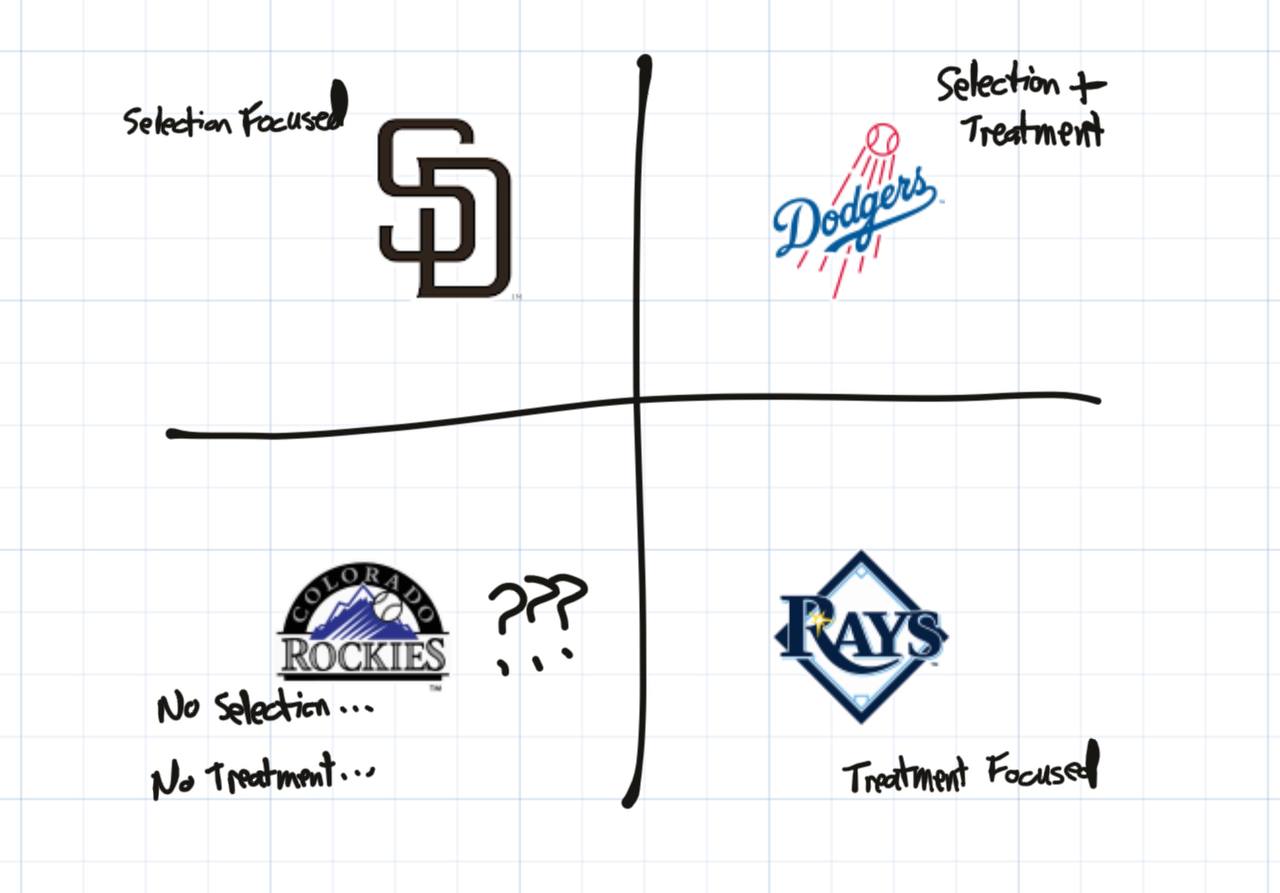

Sports are a great laboratory to study these effects because the outcomes are extremely measurable – you’re winning or you’re not – so we can observe how selection vs treatment effects play out in different sports.

In the NBA, general managers are lauded for their ability to select players, both through a draft and through free agency. NBA teams focus on building the best possible roster, and while the players of course undergo training, no amount of training is going to turn your ninth bench player into Steph Curry. NBA teams are selection effect organizations.

By comparison, in baseball, training appears to be very effective. The LA Dodgers, staffing one of the largest analytics staffs in the league, seems to be able to consistently train their pitchers, develop their batters, and turn late round drafted players into consistent major leaguers, delivering value up and down the roster.[3] Though selection is important (picking up guys like Mookie Betts and Freddie Freeman certainly helps), treatment appears to matter a lot in baseball.

Please direct any ire at this image towards Sebastian.

Basketball and baseball are both professional sports, with millions of dollars pouring into their teams and organizations, so why are they biased differently towards selection vs treatment effects?

There are a couple of interesting things at work here. First, basketball is a strong link sport, whereas baseball is a weak link sport:

I first became familiar with the concept of strong and weak games in The Numbers Game, a book by Chris Anderson and David Sally on soccer analytics. In it, they define a strong link game as one where the team with the best player usually wins. In contrast, in a weak link game, the team without the worst player usually wins.

In other words, superstars matter a lot more in basketball than they do in baseball.

Your superstar starter gets to play 30-40 minutes of every game (assuming no injuries) accounting for 12-15% of total player minutes and often 25-60% of total point share, but your best hitter or pitcher in baseball is only one of nine batters in the lineup (11% of batting) or pitching at most once every four to five days.[4]

So it’s natural to focus on selection for basketball, but in baseball – where superstars impact the game far less – improving your weakest link matters more, and we see the benefits from treatment effects.

But baseball’s benefit from treatment effects extends beyond the actual game and into the structural incentives of the league itself.

-

In the NBA, drafted and undrafted rookies sign contracts lasting only up to four years.

-

In baseball an organization can hold a new player for the duration of their minor league play, and then another six years minimum (usually seven!) once they make the majors.

All this guaranteed time with the same organization means they are more likely to see the fruits of their training labor pay off, and are therefore more willing to invest.[5] [6]

Okay enough sports. Back to startups – should you, a founder of a new fund or startup, optimize for selection or treatment effects?

Any new upstart organization with no amount of scale (in tech or otherwise) is playing a strong link game. Every individual accounts for a high percentage of the team’s output, and there is no bench. Viewed through this lens, the answer is clear: early stage startups are strong selection effect businesses.

This makes sense (and partly explains why investors care so much about early teams), but then why do larger or more mature companies tend to tilt towards treatment effects over time? The answer is ultimately cost and efficiency.

Recruiting and employing superstars is expensive and time-consuming. When your team is five people, it’s worth the effort. When your team is a thousand people, training the weakest links is likely to move the needle more than hiring a single star player.

The interplay between selection and treatment isn't just academic — it's the backbone of team building, whether in sports or startups. For fledgling ventures, every hire counts; it's all about selection.

As you scale?

Training starts to matter more.

Giffon’s perfect business may be able to do both, but most of us can’t afford to. For those of us working under constraints, determining whether you’re playing a strong or weak link game, and identifying the incentives that exist in the ecosystem you’re playing in is critical.

In the end, figuring out what game you’re playing is as important as how you play the game.

Giffon actually continues on a little longer in his answer here, saying “I think that will be close to the perfect business because I guess what I'm after is leverage and the idea of basically being able to be compensated super highly for your words is pretty close to just speaking money into existence, which I think is very close to the perfect business.” But we covered that last week, and so we’ve omitted it here. We’ve noted it here for completeness, lest you think we skipped some part of the transcript ↩︎

Many do in fact set out to do both, or at least say they are pursuing both – however, there’s always a bias towards one over the other and gun to their head, most will pretty quickly tell you which direction they are biased towards ↩︎

A draft of this sentence said delivering WAR (Wins Above Replacement, a measure of player value) up and down the lineup, but to a non-sabermetrically inclined audience, the thought of delivering WAR is a bit jarring. Honestly the phrase “non-sabermetrically inclined” itself is a bit jarring ↩︎

It’s also worth flagging that with the Luxury Tax/Max Contract Value set in the NBA’s Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA), the excess value a superstar generates is mostly captured by the incremental value a player with a max contract value generates relative to other max players, the canonical 2010s example being Mike Conley vs. Lebron James. During a 5 year period in which both Mike Conley and Lebron James were given max contracts in the NBA, Mike Conley generated 27.2 Win Shares vs. Lebron James’ 49.5 Win Shares

Sebastian can go on and on about sabermetrics after spending a good portion of his 2010s with the Houston Rockets and in that world, so do let us know if you want to see more sports related analysis! ↩︎

A bit more about the CBA in MLB – with the way arbitration and pre-arbitration works, in combination with the league’s competitive balance tax (CBT or their luxury tax; more about that here), a competent front office staff stands to generate an immense amount of outsized value (similar to Lebron James’ outsized value relative to Mike Conley) in the first 7 years of the contract. Jeff Luhnow, formerly of the Houston Astros, did a lot of very clever things in his tenure leveraging this fact. A lot of roster construction is about generating outsized value on player contracts for players in pre-arb and arbitration ↩︎

Also worth considering is the fact that a particular organization’s treatment effect might be viewed as negative – that a player for the New York Yankees may end up more damaged as a result of the soul-crushing environment that is New York Yankee fans. Note: Sebastian lives in NYC and has nothing against the Yankees. Please don’t @ us. ↩︎

Sebastian Park Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.